The Era of the Celebrity Meal – The New York Times

Advertisement

Supported by

Fast-food chains are hungry for celebrity partners to drive sales and appeal to younger consumers. The method is working.

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

By Anna P. Kambhampaty and Julie Creswell

On a Friday afternoon in the spring of 2020, Hope Bagozzi, the chief marketing officer at the Canadian coffee chain Tim Hortons, was on a Zoom call with representatives for Justin Bieber.

The agenda for the meeting? Exploring a possible partnership between the two Canadian greats.

The call was business-as-usual but took a surreal turn when suddenly, Ms. Bagozzi remembered, a black box that had been silent on the screen turned on, revealing the presence of Mr. Bieber himself. He spoke about how much he enjoyed eating Timbits, the restaurant’s bite-size doughnuts. At one point, Mr. Bieber pulled out a guitar to perform a song about Tim Hortons that he used to sing to his siblings.

“I was texting my husband saying, ‘Justin Bieber is singing to us,’” Ms. Bagozzi said, laughing. “You could’ve knocked me out of my chair.”

The result of the call was Timbiebs, a limited-edition line of doughnut holes in flavors dreamed up by the pop star and Tim Hortons’ in-house chef, which includes chocolate white fudge and birthday cake waffle. They hit restaurants in November.

Welcome to the era of the celebrity happy meal. Fast-food companies are tripping over themselves to align their products with supernova musicians and influencers in the hopes that their menu items will appeal to a younger audience. For consumers, it is a relatively cheap and easy way to connect with their favorite celebrities or influencers.

Many of the megastars the companies are courting are more than willing to cooperate, sometimes initiating the partnerships themselves. After seeing Mr. Bieber’s deal, Michael Bublé posted a TikTok video to suggest a doughnut-based collaboration of his own: Bublébits.

Dunkin’ teamed with Charli D’Amelio. There was a Lil Huddy meal at Burger King. Megan Thee Stallion has her own sauce with Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen (called “hottie sauce,” naturally). McDonald’s has created meals with Saweetie, BTS, J Balvin and Travis Scott. In November, eight people were killed and dozens were injured during Mr. Scott’s performance at the Astroworld Festival in Houston. The performer’s partnership with McDonald’s ended in 2020, according to the company.

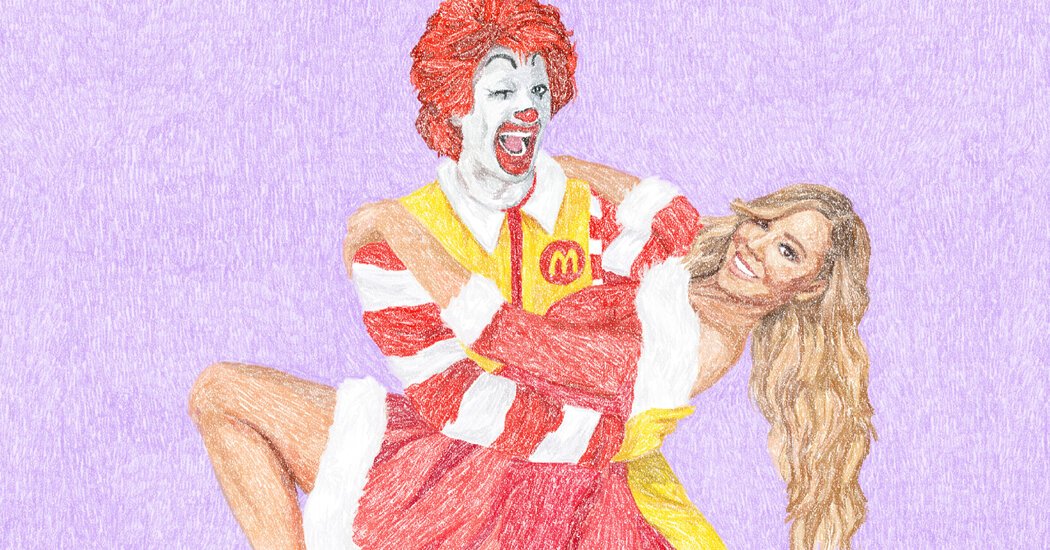

This month, McDonald’s joined with the queen of Christmas herself, Mariah Carey, to promote 12 days of deals on her favorite items, available only through the chain’s app. Despite the fact that Ms. Carey has previously said she eats only Norwegian salmon and capers, the performer’s favorite foods at McDonald’s apparently include Big Macs, hotcakes and chocolate-chip cookies.

This trend in partnerships is proving to be a boon for restaurants and celebrities, according to analysts and observers. It is also helping companies gain insights into the behavior of young consumers.

For some chains, the celebs are a powerful lure that can entice customers to download restaurant apps or join loyalty programs to get meals, discounts or even free food. During its celebrity-meal campaigns, which began in September 2020, McDonald's has seen 10 million downloads of its app, a significant jump.

“It’s very clear that McDonald’s is using celebrities to drive the younger generation to its app as a great touch point for engagement” with Gen Z, said Lauren Hockenson, a product marketing manager at Sensor Tower, which tracks app downloads and ad spending.

By offering rewards and a loyalty program, she said, McDonald’s is “hoping that the same consumer will come back to the app and find that McDonald’s is a cool, savvy, hip place to grab food.”

These celebrity partnerships are also helping brands gain access to where millions of digital natives spend tons of time: Instagram, TikTok and other social media platforms.

“If you think about the target we’re focusing on, which is youth and youth culture, that’s where they’re living,” said Jennifer Healan, the vice president of U.S. marketing, brand content and engagement for McDonald’s.

Even before Dunkin’ teamed with Charli D’Amelio, it was clear to her followers on TikTok (of which there are currently over 130 million) that the 17-year-old brunette liked the chain’s drinks; she frequently posted videos and clips of herself sipping coffee while dancing or showing off her outfit of the day. “There wasn’t a day she wouldn’t go without her Dunkin’,” said Ali Berman, the head of digital talent and a partner at United Talent Agency, which represents Ms. D’Amelio.

In September 2020, when Dunkin’ debuted the Charli — a Dunkin’ cold brew coffee with whole milk and three pumps of caramel swirl — and Ms. D’Amelio advertised the drink on her social media platforms, the result was a record in daily active Dunkin’ app users, company executives said in an earnings call last year. (The company did not respond to requests for comment.)

For Dunkin,’ the partnership was straightforward. The company didn’t have to spend weeks or months whipping up new flavored coffees or dreaming up clever new names. “We took an existing product, renamed it after her and positioned it to appeal to a younger consumer,” said Scott Murphy, president of Dunkin’ Americas, in the same earnings call. (Dunkin’ later introduced another D’Amelio drink, the Charli Cold Foam, which was simply the Charli with some cinnamon sugar and cold foam added to it.)

TikTok was soon flooded with free promotion for Dunkin’, as young people posted videos of themselves sipping Charlis. Similarly, when McDonald’s was selling its Travis Scott meal, the rapper’s fans recorded videos of themselves blasting his song “Sicko Mode” as they ordered, then shared the videos on TikTok.

“Young people become these unintentional marketers,” said Frances Fleming-Milici, the director of marketing initiatives for the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health. “Companies don’t have to pay for that organic content and all the TikToks that people make.”

Often, the advertising that comes from social media engagement is the goal of these campaigns. Megan Thee Stallion advertised her partnership with Popeyes, which is owned by Restaurant Brands International, this past October with a five-minute-long YouTube video, “Hottie Sauce Mukbang.” On Instagram, she shared a video of her best friends ordering and trying the sauce.

Even before the sauce was available in Popeyes restaurants, “we started to see an immediate reaction from people by just her posting and us releasing the press kit,” said Bruno Cardinali, the chief marketing officer of Popeyes. “Social media was the thing in this campaign.”

Those app downloads and sign-ups also allow the fast-food companies to collect customer data. Restaurant chains like McDonald’s are trying to track how customers are ordering, and specifically determine where, at what time, how frequently, and how they pay, said Kelly Martin, a marketing professor at Colorado State University, who researches customer-data privacy issues.

Starbucks has been particularly successful with its loyalty rewards program, Dr. Martin said. “With the customer data they have been able to collect through their program, they’ve been able to dramatically increase the value per customer.”

The goal of the data collection for most restaurants is to alter customer behavior. It could be used to send push notifications with special deals that are designed to get customers to return to the restaurant more frequently or to purchase more items when they do return, said Kate Hogenson, principal consultant at the Mallett Group, a loyalty consulting firm. She sees that as a good thing in this case.

The interests of these companies and their customers are “aligned right now,” Ms. Hogenson said. “If I’m McDonald’s and I’m gaining buzz from that Saweetie meal, and it’s drawing people in, now I want them to join my loyalty program and I’ll track them better, but I’ll compensate them with free stuff.”

Critics say the partnerships, which have been largely targeted at a younger audience, should be pointed toward healthier food options. A medium order of Ms. D’Amelio’s cold foam drink at Dunkin’ has 50 grams of sugar. The Lil Huddy meal at Burger King doesn’t stop with a spicy chicken sandwich and mozzarella sticks, it also comes with a chocolate shake. Including the shake, it clocks in at over 2,400 calories and nearly 100 grams of fat.

“Celebrity endorsements are particularly powerful with children,” said Josh Golin, the executive director of Fairplay, a nonprofit focused on how marketing affects children. “They begin to associate that celebrity with the brand, and they want that junk food even when it’s not being directly advertised to them.”

Indeed, while children may be able to discern a commercial for a product that interrupts a show on television, the lines get blurry for them when it comes to paid content on social media, Mr. Golin said. It can be difficult for children to guard themselves against promotion that comes from an influencer they follow, he added.

Spokeswomen for McDonald’s and Restaurant Brands International, which owns Popeyes, Burger King and Tim Hortons, said in emails that they market responsibly to children under the age of 12 and that they offer healthier options. “As it relates to our celebrity-inspired meals, we understand these can be popular with younger guests and our intention is that they be enjoyed as a treat during the limited period through which they are offered,” added Leslie Walsh, a spokeswoman for Restaurant Brands International.

The celebrities and fast-food brands would not say how much money the celebs are making from these deals, and those contacted for this article declined to respond.

That kind of success means that this trend isn’t going to disappear anytime soon. Indeed, for the celebrity and influencer class, there are endless tie-ins.

When agents at A3 Artists Agency discovered one of their clients, the YouTuber Larray, worked at Subway as a teenager, they immediately thought: partnership.

According to Jade Sherman, a partner and head of digital for the agency: “We reached out to Subway and were like, ‘You guys have to do something.’”

Advertisement