To Open Homeless Shelters, N.Y.C. Relied on Landlord With Checkered History – The New York Times

Advertisement

Supported by

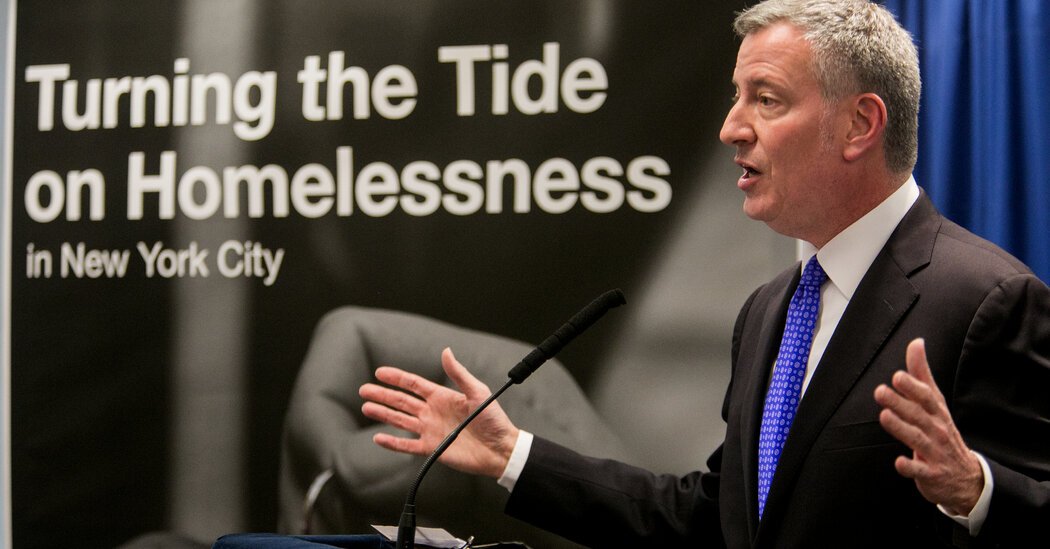

Mayor Bill de Blasio promised to revamp the homeless shelter system, but some of the main players have not changed.

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

By Amy Julia Harris

In 2015, David Levitan’s company was listed as one of New York City’s worst landlords. At an apartment building he owned in the Bronx, which the city used to house homeless people, inspectors found a host of violations, including a rat infestation, rotting wooden floors and elevators that went out for days at a time.

At a different building Mr. Levitan owned next door, an internal stairway collapsed, inspections showed. In Queens, tenants in another of Mr. Levitan’s buildings said they went days without heat and hot water, and they complained of bedbugs and peeling lead paint.

Those were the kinds of conditions Mayor Bill de Blasio aimed to eliminate when he announced a plan in 2017 to revamp the city’s homeless shelter system. The city would stop placing people in landlords’ rundown apartments and instead would open dozens of new shelters managed by nonprofit organizations to provide better living spaces and services, he said.

But in implementing the plan, Mr. de Blasio’s administration has relied on one building owner more than any other: Mr. Levitan.

Many nonprofit groups do not have their own spaces and must rent from private landlords. Nearly a third of the new shelters that have opened so far are in buildings owned by Mr. Levitan, The New York Times found. His extensive role in Mr. de Blasio’s initiative, which has not been previously reported, demonstrates how a small group of landlords holds outsize influence in New York’s shelter system, turning a crisis that has reached record numbers into a profitable industry.

Mr. Levitan not only owns the buildings; he also operates a maintenance company to service the properties, generating millions of dollars in additional revenue. In two instances, The Times found, Mr. Levitan required the nonprofit groups renting his buildings to hire the maintenance company, an apparent violation of city bidding rules.

New York City spends more than $2.6 billion a year on homelessness — a number that has soared in recent years. This year, The Times has documented how executives at many nonprofits that run shelters have enriched themselves through high salaries, nepotism and questionable contracts.

A sizable chunk of the money going to nonprofits, however, ultimately ends up in the hands of the owners of the properties that the groups rent for shelter space.

Mr. Levitan is one of a handful of landlords who have worked with the city for years and now own the majority of the buildings that house Mr. de Blasio’s new shelters. The city had refused to disclose the addresses of shelters and their operators in recent years, but The Times obtained the data last month after filing a public-records lawsuit in June.

Shimmie Horn, whose family was long involved in renting hotel rooms to the city to house the homeless and who operates luxury hotels in Manhattan, and Daniel Rabinowitz, a real estate developer, also own a significant number of the buildings occupied by the new shelters.

But Mr. Levitan, known as Didi, owns the most: 14 of 49 new shelters that have opened during Mr. de Blasio’s tenure. Mr. Levitan purchased the buildings through limited liability companies and often with business associates; The Times identified his role by analyzing city buildings records, incorporation documents and legal filings. Mr. Levitan confirmed he owned the properties with partners.

A spokesman for the Department of Social Services, the city agency that oversees shelters, said the nonprofits — not city officials — chose Mr. Levitan’s buildings and then submitted their proposals to the city. He said the de Blasio administration had expanded the number of landlords providing shelter space to more than two dozen and said Mr. Levitan’s newer properties had far better conditions than his older ones.

“The provision of shelter is challenging work for all involved — including providers, developers, property owners, staff and clients alike — and we are enormously grateful to those organizations that are willing to see this work through,” said the spokesman, Isaac McGinn.

In an interview with The Times, Mr. Levitan said he still often brought city officials properties for tentative approval before working with a nonprofit group to pitch the deal to the city and finalize a contract. He strongly defended his track record as a landlord.

Mr. Levitan said that while some of his previous buildings had issues, he had worked to fix any open violations. He said he renovated the buildings he bought for the new shelters, and they all had passed inspections.

“We’re the Cadillac of all shelters, and we’re proud of it,” Mr. Levitan said. “We run really good shelters, and we have a great reputation, thank God.”

Renting buildings to the city comes with headaches, including late payments and a cumbersome bureaucracy, and many landlords are not interested. At the same time, New York is under an uncommon and decades-old court order to house every homeless person.

For decades, the city has gobbled up space in former hotels, warehouses and factories from the same building owners, over and over.

“Housing is in such short supply, especially for shelters, that a select few [landlords] have cornered the market,” Jahmani Hylton, a former deputy commissioner for the Department of Homeless Services, said in a 2019 interview.

In addition to the buildings housing new shelters, Mr. Levitan also owns dozens of other properties around New York that predate Mr. de Blasio’s initiative and are still used as shelters, a Times analysis shows.

It is difficult to determine how much money Mr. Levitan and his business partners earn from their sprawling enterprise. But records for one of his properties show the financial potential: He and his partners bought one building in College Point, Queens, for $12 million in 2018 through a company that now generates $2.9 million a year in rent.

In 2017, the state comptroller released a report saying New York’s system for finding shelter space was so inconsistent and jumbled that auditors could not tell if the city was paying reasonable rates. New York was largely at the mercy of landlords with “no choice but to accept the cost,” the review found.

Mr. Levitan said working with the city is a gamble: Renovating buildings is expensive, there is no guarantee the city will want them and the properties must meet a host of city and state regulations. He said shelters suffer more wear-and-tear than other apartment buildings, and maintenance is often more expensive.

“It’s a very risky business that most people don’t want to get into,” said Mr. Levitan. “If the city decides to cancel the contract, you’re stuck holding the bag.”

In response to the state comptroller’s report, the city said it would conduct analyses to ensure it was paying reasonable amounts. The Times sought to obtain these analyses through a public-records request more than a year ago, but the city has not released them.

Mr. Levitan said he began working with the city in the late 1990s, when he and his business associates converted a hotel in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, into a homeless shelter. His portfolio expanded as homelessness grew in New York and the city tried different approaches to the problem.

“They needed space; they reached out to different landlords, and as the need grew, we grew,” he said.

Starting in the early 2000s, Mr. Levitan placed homeless people in hundreds of private apartments scattered throughout his rental buildings. He made about $1,000 a month for each of those units, he estimated in a 2002 interview with The Times. Mr. de Blasio has phased out that method for housing the homeless.

In addition to owning dozens of buildings used as shelters, Mr. Levitan has another source of steady revenue: He operates a for-profit maintenance company, Liberty One, that performs upkeep at many of his properties. At the building he bought in 2018 in College Point, Queens, the maintenance company was paid more than $800,000 in the last fiscal year — money that also comes from the city, according to budget documents.

City contracting rules require the nonprofit groups running shelters to control costs by soliciting at least three independent bids for services. But in two cases — identified in an independent audit and a lease — Mr. Levitan required nonprofit groups to use his company without bidding, The Times found.

Mr. Levitan said there was “zero requirement” that nonprofit groups hire his company. However, Mr. McGinn, the city spokesman, said a review, done in response to questions from The Times, had discovered such a provision in one group’s lease. He called the arrangement inappropriate and said it would be changed.

Mr. Levitan also owns an extermination company used in at least one of the new shelters, according to city records and a corporate disclosure. When ants infested some rooms in the building in the Mott Haven neighborhood in the Bronx, his company, Squash Exterminating, was called in to help.

Mr. Levitan said he started both the maintenance and the extermination company to streamline operations and provide better services.

In the more than two decades that he has been enmeshed in New York’s homelessness machinery, Mr. Levitan has been repeatedly accused of neglect and poor conditions at some of his buildings.

In 2014, elected officials battled a plan to open a permanent shelter in Elmhurst, Queens, in the former Pan American hotel, which was owned by a limited liability company connected to Mr. Levitan. Residents of that building, which housed hundreds of homeless families, reported infestations of bedbugs, peeling lead paint and a lack of heat or hot water. The New York Daily News published a video, provided by tenants, of a growing horde of rats near a children’s play area.

The city comptroller, who oversees New York’s finances, rejected the contract several times over the health and safety violations before finally approving it. The city still uses the building as a shelter, records show. Mr. Levitan said that the apartments have been renovated and that the building is now “in beautiful shape.”

In 2015, Letitia James, then the city’s public advocate and now the state attorney general, included one of Mr. Levitan’s buildings on her annual list of the city’s worst landlords. The building along Southern Boulevard in the Bronx had accumulated more than 250 tenant complaints and city violations. Inspectors found faulty elevators, leaking ceilings, chipping lead paint on the walls and rotting wooden floors in apartments.

“It was a tough building,” Mr. Levitan said in the interview with The Times. He said he later sold it.

Mr. Levitan owned the building next door as well, and it was also used as a homeless shelter. Sharon Cepeda, who moved there in 2012 with her partner and three daughters, said there was such a severe infestation of rats that they would devour the plantains and potatoes she had left on the counter. She said the ceiling in her bedroom collapsed, and the hallways were strewn with trash.

“The conditions there were horrible,” Ms. Cepeda, who ultimately filed a lawsuit after slipping in a puddle of urine in a hallway, told The Times in an interview. “He didn’t maintain the building at all. He was a slumlord, he really was.”

At another building Mr. Levitan owns in Far Rockaway, Queens, which the city has used as a homeless shelter since 2014, residents interviewed by The Times earlier this year said they had developed coughs and breathing problems.

“It was disgusting,” said Tori Morton, who lived in the shelter from 2019 until this summer. She said she bought four cans of Raid each week to keep the cockroaches in her room at bay and repeatedly complained about the mold snaking along her ceiling. “They just painted over it,” she said. Mr. Levitan’s maintenance company is responsible for upkeep at the site and has been paid more than $1.7 million since 2019, records reviewed by The Times showed.

Mr. Levitan said he visited the shelter last week and had not noticed any problems. Mr. McGinn said that the city had worked intensively to clear violations at the building and said there were no outstanding issues.

The 14 buildings that opened under the mayor’s initiative have not racked up the serious violations that have plagued other buildings owned by Mr. Levitan, according to a review of city records. All the new buildings have also passed state inspections, records show.

Still, in interviews, several residents at the new shelter in College Point have said that while the building was renovated with new appliances, the maintenance company has been slow to respond to some of their concerns.

Carmen Morales, who said she had moved into the shelter about two years ago, said the bathrooms often shut down, and the hot water in the shelter frequently went out. (Mr. Levitan said he had not received official complaints about the hot water. He said there was a problem with the water heater several months ago, which was promptly resolved.)

“We try to complain, but they don’t do nothing,” Ms. Morales said.

Sean Piccoli contributed reporting. Susan Beachy contributed research.

Advertisement