A global clash over technology dominance is mounting – TechCrunch

When it comes to state-sponsored corporate espionage, it’s easy to dismiss seemingly unrelated actions as random, unimportant or irrelevant.

Consider the following: China is flooding Silicon Valley with billions of investments in AI, biotech, autonomous vehicles, quantum computing and semiconductors. They’re investing huge sums in basic R&D in those same areas. There are increasing concerns about professors at U.S.-based universities hiding their ties to Chinese research institutions — just last month, a Harvard professor was convicted on federal charges.

And, as most technology CEOs in these sectors know, there is an unrelenting effort by firms connected to the People’s Republic of China to compromise their people, networks and systems. Malign actors are hacking into companies, large and small, and adopting blended operations that incorporate non-traditional intelligence collection activities to acquire information on advances in emerging technologies.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation reports that it opens an investigation into Chinese government actions every 10 hours.

When you understand that the PRC is engaged in a generational effort to win dominance across the technology sector – military and civilian alike – the pieces of the puzzle start to click into place.

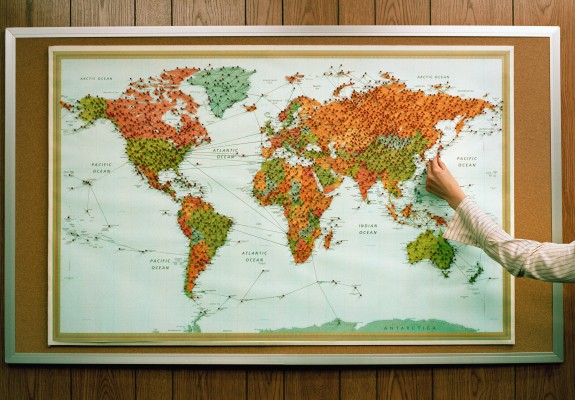

Today, our adversaries are playing a deadly serious game of strategic competition and espionage without rules, without limits, and without end. In recent years, the PRC has constructed a global system to analyze, target and acquire foreign technology and the scientists, engineers and companies working on them to advance their own national strategic objectives.

The U.S. and the West are just starting to wake up to the threat. The U.S. National Counterintelligence and Security Center recently acknowledged that “the PRC employs a wide variety of legal, quasi-legal, and illegal methods to acquire technology and know-how from the United States and other nations.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation reports that it opens an investigation into Chinese government actions every 10 hours. Canada is going to require all of its scientists to be screened to ensure government funds are not supporting adversarial R&D programs. And Japan recently minted a new minister of economic security — a cabinet-level post — to secure the country’s supply chains, intellectual property and critical infrastructure from economic espionage.

Even NATO recently stepped into the battle, calling on allies to block Chinese investment and noting that resilient “critical infrastructure and industries” are enshrined in the alliance’s founding treaty. This is a historic declaration. In today’s geopolitical battle, corporations are on the front lines whether they like it or not.

In response, Washington, Brussels and Tokyo are likely to ratchet up efforts to curb China’s access to early-stage tech startups, especially those developing “emerging” or “frontier” technologies. This will impact funding for tech startups and venture funds alike. Washington has already put in place tools to block or unwind China’s access to U.S. technologies in the form of FIRRMA and the Export Control Reform Act of 2018. Regulators are going to use these tools in earnest to review investments in early-stage tech companies, M&A and technology transfers.

But this is not enough. Governments and companies in the free world must take active, sustained and effective measures to counter the threat.

The first step must be for Western governments to rise to the challenge and recognize industry as a battle-space. Doing so will catalyze a change of mindset for corporate boards, as the past decade has seen many U.S. companies adopt a globalist mentality with nominal interest in helping to advance Western values.

The next step will require governments to define the strategic industries and emerging technologies that are critical to winning this competition. The U.S. Department of Commerce has taken a step in this direction with the Export Control Reform Act of 2018. Requiring companies to do the same will be critical to ensuring a unified private-public bloc that keeps critical know-how and IP from proliferating to adversaries. Boosting funding for R&D and creating markets, including within the public sector, will help to offset the short-term costs companies incur.

Finally, all of the existing and forthcoming legal and policy prescriptions are for naught if the U.S. can’t get allies in Europe and Asia on board in creating a unified legal framework for investment screening and export controls. This presents a true leadership opportunity for the United States, and we must rise to the occasion and rally the free world to come together.

Ultimately, this geopolitical clash will create frustration among some tech executives, startup founders and venture capitalists. This is because strategic competition, on some levels, runs counter to the tech world mantra of the free flow of people, capital and ideas.

But it is Western values and rule of law that created these ideas. And they’re worthy of our protection not only for our continued benefit, but for future generations.