World map shows which nations met 40% vaccine goal — and which didn't : Goats and Soda – NPR

Nurith Aizenman

What went wrong?

At year’s end, that’s the question being asked about the global effort to make sure that all countries get vaccines against COVID-19.

Almost as soon as the pandemic began, the world’s leading health organizations joined forces to ensure an ample supply of the vaccines for all nations regardless of income level. The program they created is known as COVAX – short for the COVID-19 Global Access Facility. It was supposed to pre-purchase doses from the manufacturers while the vaccines were still being developed, and then – once the doses became available – distribute them to countries according to their need and charge according to their ability to pay, with the lowest income countries getting the doses for free.

Loading…

Yet as 2021 comes to a close, and the omicron variant spreads across the globe, the vast majority of people in lower income countries remain unvaccinated.

NPR spoke with two public health leaders with unique perspectives on this issue.

Seth Berkley is head of GAVI the Vaccine Alliance — one of the organizations that formed COVAX (along with the World Health Organization, UNICEF and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations or CEPI.) Krishna Udayakumar directs Duke University’s Global Health Innovation Center – which helped create an independent hub for tracking both the progress and the obstacles to COVID vaccine access.

Here are eight takeaways:

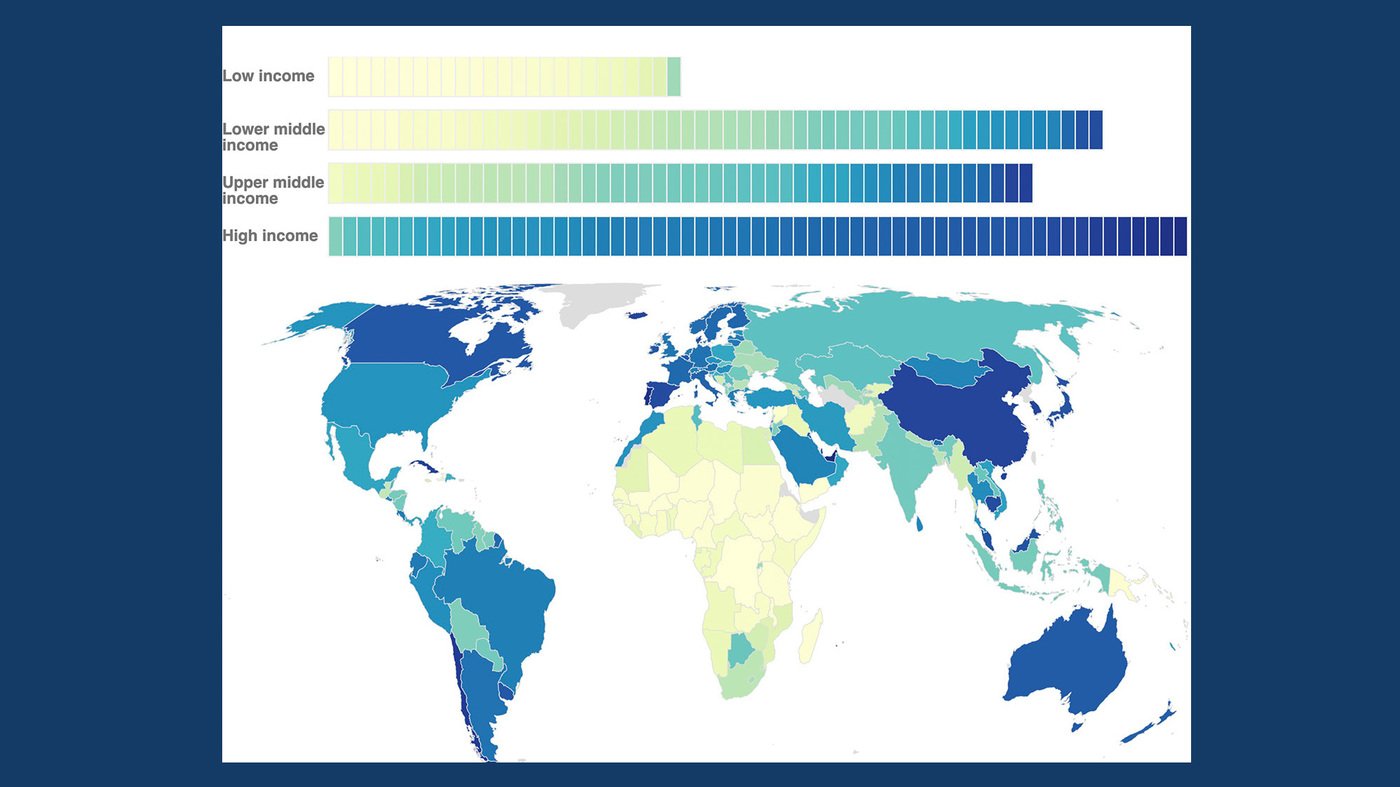

In September President Joe Biden proposed a global goal of vaccinating at least 70% of the world’s population by autumn of 2022. The United Nations and the World Health Organization argued the target should be met even sooner – by mid-2022 – and that by the close of 2021 at least 40% of people in every country should be vaccinated.

It’s now clear that more than 90 countries will miss even that more modest 40% target. “Some of these countries are in South and Southeast Asia, as well as some in Central and South America,” notes Udayakumar. “But the majority are in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

What’s more, he says, these countries haven’t just missed the 40% target – they are often well below it. In the lower-income countries that qualify for free or highly subsidized vaccines from COVAX, “the average vaccination rate is closer to 20% than 40% right now,” says Udayakumar. And in sub-saharan Africa, many countries are stuck at vaccination rates in the single digits.

“It’s quite concerning because we know that this is leading to exactly the type of situation where infections are raging around the world,” says Udayakumar. “We’re losing lives unnecessarily. We’re seeing enormous economic damages. But it’s also setting up the petri dish in essence to create new variants over time. All of us remain unsafe so long as we’re not doing everything possible to more aggressively vaccinate.”

As disappointing as the progress has been, says Udayakumar, “we would be in a worse situation than we are right now if COVAX didn’t exist.” To date it has distributed more than 800 million doses of vaccine to more than 140 countries – “many of which wouldn’t get access to vaccines as quickly or in the amounts that they have otherwise.”

Udayakumar says COVAX has “fallen short” due to “naive thinking” behind its set up – specifically a failure to anticipate that wealthy countries were going to rush to buy up virtually all of the vaccine supply from manufacturers through pre-purchase agreements.

GAVI’s Seth Berkley recalls how fierce the contest was. “We were competing against countries that had opened their treasuries and had the [clout] to demand that vaccines flowed to them,” he says.

The result was that once vaccines started becoming available, that early supply was almost entirely earmarked for wealthy countries. And vaccines are still only slowly making their way to the rest of the world, as wealthy countries continue to bring in many more doses than they are actually using each month.

Indeed, says Udayakumar, the same problem has hampered a similar effort by African nations to band together to buy vaccines for their continent. The initiative – called the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, or AVATT – “has agreements for hundreds of millions of doses. It has been able to deliver many fewer than that,” notes Udayakumar. “It’s a matter of having paid for doses that haven’t arrived yet. So the real challenge comes back to decision-making by high-income countries, as well as the manufacturers themselves, when they have sold three, four or five times what they can produce at any point in time, they’re having to make decisions about who is getting doses first. And almost across the board those doses have gone to high-income countries first.”

Adding to COVAX’s difficulties, says Berkley: “You’d want to have financing on day one. We started with zero, and of course that meant we couldn’t put orders in early,” he says.

Eventually COVAX was able to raise funds from donor countries and organizations. But, says Berkley, “it took us until the end of [2020] to get the first $2.4 billion in commitments.” Even at that point the cash actually delivered to COVAX was “very low,” he adds. “I think $400 million.”

If COVAX had been fully funded from the start, says Berkley, “even if you couldn’t compete with the U.S. treasury or the European union, you might be able to do technology transfers.” Specifically, COVAX could have more quickly expanded the pool of vaccine suppliers by identifying manufacturing plants with the capacity to produce vaccines – then providing them the funding and assistance to learn how to produce some of the vaccine candidates.

As it was, COVAX only had the resources to work with a few companies, says Berkley – the most prominent of which was Serum Institute of India or SII. Then, last spring, soon after SII began producing doses of AstraZeneca vaccine, India was hit with a massive wave of cases. The government mandated that all of SII’s COVID vaccines be redirected for India’s domestic use. “It meant that all of a sudden, the 350 million doses we had expected to have for [COVAX-supported] countries wasn’t there,” notes Berkley. The situation delayed the roll-out of vaccines to African countries in particular by months. And although India lifted the export ban last October, SII is only just ramping up the number of doses it is sending to COVAX.

As problematic as COVAX’s reliance on SII has proved, says Berkley, “If today I was doing it, I would do exactly the same thing.” That’s because faced with such limited funds, COVAX had to go with the company most likely to be capable of scaling up quickly. SII well suited to doing so – “it’s the largest manufacturer in the world [of vaccines] by volume,” notes Berkley. But there also simply weren’t that many other candidates.

This paucity of vaccine makers in developing countries needs to be fixed, says Udayakumar. “The place where the vaccines are manufactured makes a huge difference,” he says. “We’ve seen manufacturing that’s been mostly in high-income countries as well as in India and China. And those are the regions that have gotten access to vaccines most quickly. We need now much more sustainable vaccine manufacturing across Sub-Saharan Africa as well as Latin America and south and Southeast Asia.”

What it will take to make that happen is now the subject of lively and complex debate. But Udayakumar says at best it will take “months to years” to achieve.

To ease the current supply crunch COVAX is facing, it would be helpful for wealthy countries to to ramp up donations of excess vaccines that they’ve already purchased, says Udayakumar. And already, he notes, “almost 2 billion doses of vaccine have now been pledged to be donated mostly from high-income countries with over 1.1 billion of that pledge coming just from the U.S The U.S. has also shipped more than 300 million doses of donated vaccine, which is more than every other country combined at the moment.”

Unfortunately, adds Udayakumar, “maybe a quarter of what’s been pledged has actually been shipped – much less gotten to the countries that need them.”

Berkley adds that another difficulty is that those donated doses arrive “sometimes with short shelf life. Also, he says, “one of the challenges is to try to make sure those donations ideally, are not earmarked [for specific countries] … and that we get enough time for countries to know they’re coming, so countries can plan.”

While supply delays remain the biggest obstacle to increasing vaccination rates in lower income countries, Udayakumar says he’s optimistic that the problem will soon be eased.

“I think there are at least some glimmers of hope on the horizon in that the supplies are increasing rapidly.”

More worrying, he says, is a continued lack of adequate financing and preparation for the logistical task of administering doses. “The greatest challenge is less about getting the vaccines from manufacturers to airports, and now much more about getting vaccines from airports to arms.”

An earlier version of this map identified Crimea as part of Russia, which invaded and annexed Crimea in 2014. The majority of the international community has denounced Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea as illegal. The map has been revised and now includes Crimea as part of Ukraine.

NPR thanks our sponsors

Become an NPR sponsor