'Small World' by Jonathan Evison book review – The Washington Post

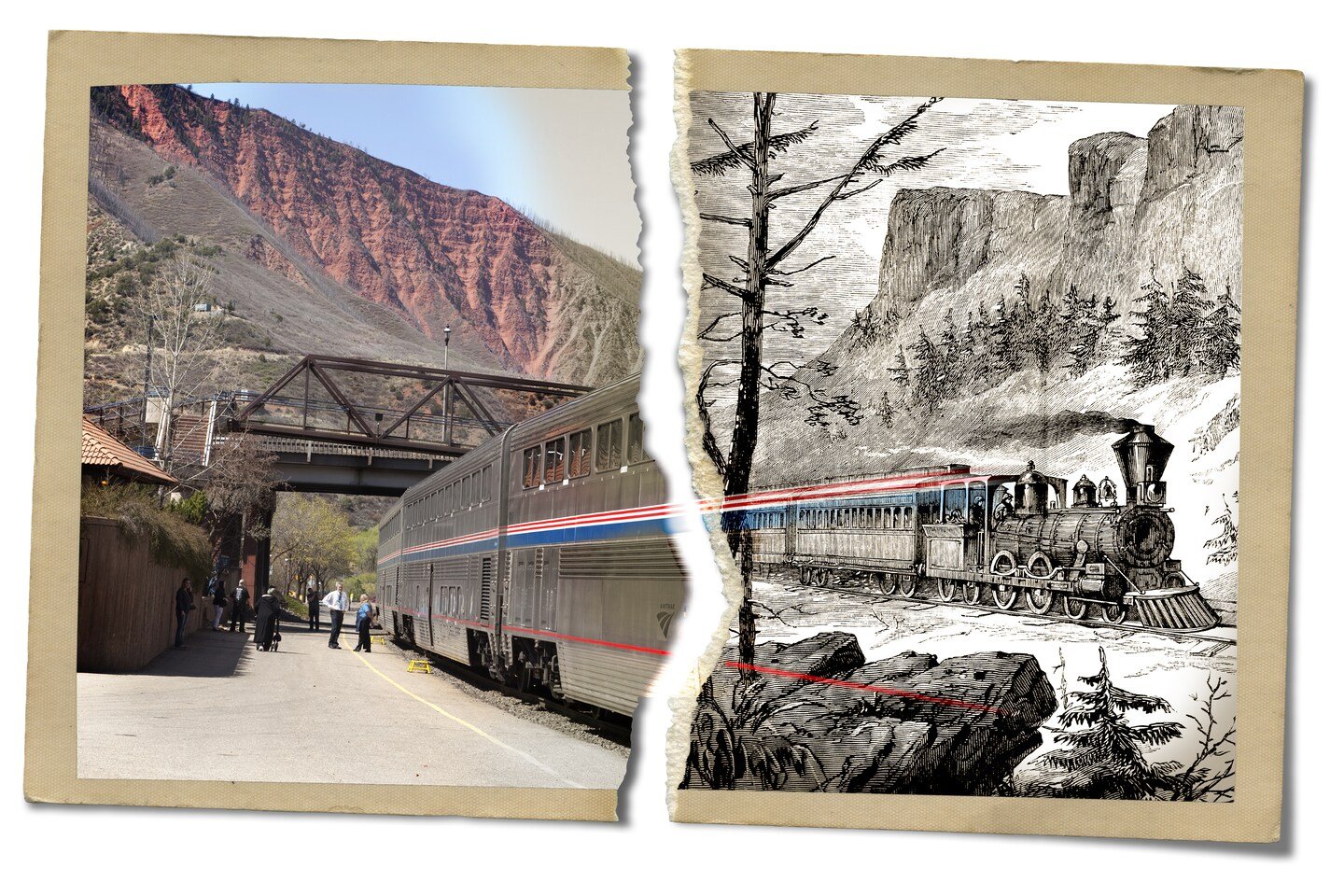

On May 10, 1869, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was marked at a ceremony on high ground in Utah. “The great men, those architects of American progress, [David] Hewes and [Leland] Stanford, delivered speeches,” writes Jonathan Evison in his epic new novel, “Small World.” “They spoke of overcoming the impossible and of shrinking the world one track at a time. At last, they raised their silver hammers above the golden spike, and though they both missed their mark, they pronounced the job complete.”

The fumble is a fine detail, drawn from life, that captures in miniature the imperfection Evison finds at the heart of the American experiment. In his telling, the rise and fall of the railroad over the ensuing century and a half just inscribes that imperfection on a grander scale, the crumbling of infrastructure once dazzling (“Dad, we go eighty in the Prius”) proving to be a good metaphor for a country faltering in its execution and uncertain of its direction.

Sign up for the Book World newsletter

Like the missed spike, that which glitters in “Small World” tends to disappoint. Golden is the “promise of America” made to Irish twins landing in New York aboard the Golden Door; to a Chinese prospector arriving in San Francisco in search of the Golden Mountain; even to a pair of Indigenous lovers in California surveying a “wide golden valley.” But America is also, as one of the lovers observes, a “land of broken promises.”

Much as he did in his earlier novel “West of Here,” Evison braids together story lines from different time periods — in this case the mid-19th century and the present day — to create a kaleidoscopic series of juxtapositions. We meet Wu Chen, who in 1851 witnesses the murder of his associates at the hands of White men, retrieves their hidden gold, marries a grocer’s daughter and becomes a supermarket mogul. In 2019, six generations later, Jenny Chen handles corporate layoffs, chides her spoiled sons and wonders if this is all there is. Luyu Tully is a Miwok woman whose rootlessness in the 1850s is echoed by her descendant Laila, who flees her home, an abusive relationship and a waitressing job in Northern California 170 years later. In antebellum Illinois, an enslaved man called Othello escapes, renames himself George Flowers and elopes with his free lover; a century and a half later, single mom Brianna Flowers works hard to provide for her basketball-star son. Meanwhile, Finn Bergen, present in Utah in 1869, turns out to be the first of four generations of railroad Bergens, the last embodied by 63-year-old Walter, whose momentary negligence on the day of his retirement ties the various present-day plotlines together.

10 noteworthy books for January

“Small World” is a hefty, old-fashioned novel. In a steady cavalcade of action, we encounter dramatic changes of fortune; love, murder and betrayal; tragedy and whimsy. Its short chapters and sheer eventfulness keep the story chugging along, while its (somewhat mechanistic) plotting creates enough suspense to hold the attention. It’s broad-brush, well-intentioned stuff, with an ethnically diverse cast of characters offering, through close third-person narration, wry, sometimes caustic commentary on the nature of American opportunity (“Somebody had to pay the passage for the lucky ones”).

Evison’s writing is best when his powerful feelings for injustice and privilege grate against one another, producing some effective ironies. “Um, your people seem like they assimilated pretty well to me,” one character says to his wife. “The Chinese footprint is all over this city. You’ve got your own neighborhood. Where’s Irishtown?” “Exactly,” she replies.

Sometimes, though, he drifts into a more sententious, editorial register. “To be Chinese in America was to be separate, to be displaced,” he states. Later, echoing himself: “To be Miwok, to be Indian at all, was to live always with the idea of homelessness.” These ideas, though sympathetic, demonstrable and central to the book’s moral philosophy, feel more like learning moments than storytelling. That the characters tend to be, at heart, straightforwardly good or bad only compounds the didactic effect.

The 10 best books of 2021

There are some lyrical touches, such as when Othello, having fled his captor, “laid his body down in the grass beneath the star-spangled bowl of the moonless night.” But Evison’s prose is often marred by hackneyed phrases of the “sting of tears” variety — hearts beat “at a gallop”; a resolute person is “an unstoppable force of nature.” He can also be a little loose, repeating expository phrases and sometimes missing the right historical tone.

“Small World” feels like a big statement about America — Evison has even called it his attempt at the Great American Novel — and it’s filled with weighty ideas and worthy commentary on oppression and racism. It has some touching moments, and Evison has a good grasp of the changing significance of things. But it ultimately feels like a missed opportunity. It’s odd that the contemporary chapters, set in 2019 and 2020, barring scattered references to identity politics, don’t tackle the wider cultural crises of the Trump era. And the book’s moral simplicity rather leaches it of urgency and vigor. Though it’s ambitious in its conception, it’s a shame that the world Evison created isn’t larger.

Charles Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, films and music.

By Jonathan Evison

Dutton. 480 pp. $28

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

The most important news stories of the day, curated by Post editors and delivered every morning.

By signing up you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy